My family begins in America with an adolescent girl named Binah, my 6th great grandmother, an enslaved African who had her first child, a boy, at the age of 12 in 1778.

Binah was owned by a man named Darling Jones who owned enslaved Africans, not to sow crops, but for the purpose of breeding. Having children at 12 or 13 wasn’t at all uncommon for someone owned by a breeder. Women who lived in these conditions were expected to have four or five children by the time they were twenty. Some more successful breeders even implemented quotas promising to manumit an enslaved African woman after she gave birth to her 15th child. By 1832, Virginia was considered the Negro-raising state in the Union, exporting as many as six thousand enslaved Africans a year due specifically to breeding.

During the time Binah was owned by Darling Jones she had three sons. At some point, Binah was sold to another man named William Goodwyn, and from there she moved to the Goodwyn cotton plantation in the Camden district of South Carolina and worked as a field slave.

It was here, on the Goodwyn Plantation, on May 16, 1781 that Binah had her first daughter which she named her Tenah, (pronounced Teh-nay) after her African Grandmother. Tenah is my 5th great grandmother.

When William Goodwyn died, his last will split Tenah’s family among William Goodwyn’s five children, William Jr., Uriah, Francis, Amy and Kezia.

When Tenah was 15 she too was bred just like her mother before her. And like her mother Binah, her first child was a boy. Tenah named him “little Frank” presumably because the child’s father was Big Frank, one of the slaves that were rented out to the William Goodwyn, to breed with Tenah. This was customary for Slave-owners to stud the biggest, strongest, healthiest slaves, literally lugging them around from plantation to plantation impregnating young enslaved African girls. Since the children of a slave carried the condition of the mother, breeding was the cheapest way to acquire new slaves without incurring the cost of purchasing a slave from the market which could cost as much as $21,000 today for a single slave.

It is unclear how many children Tenah had through this breeding, but in 1813, when Tenah was 30, she had her first daughter, Sarah. Sarah is my fourth, great grandmother. Tenah named her daughter Sarah after her mistress Sarah Goodwyn, the widow of William Goodwyn Jr. At some point, Tenah and her family had been given to Sylvia Poythress Goodwyn, the daughter of William Jr. and Sarah Goodwyn, who had married James Adams. Tenah and Sarah were now living on the Adams plantation in what is now Hopkins, South Carolina where my family lives to this day.

Sarah was much lighter than all of Tenah’s previous children although no one ever talked about it. No one ever talked about her complexion or her features because if it wasn’t decided whom her father was it certainly was obvious whom her father wasn’t. Her father wasn’t Big Frank, Big Joe, Big Bill or whatever “Big” slave was being rented at the time. Her father was an Adams, as she clearly resembled all of the Adam’s children.

Although Sarah initially started out working in the fields like her mother, Sarah was soon spared the incredibly difficult life working the fields to work in the big house. In situations like this when the parentage of Sarah is undoubtedly not another field slave, a move like this can often be an indicator of whom her true parentage is, although not always. Usually this is done because the Master knows that this is his son or daughter and this was his way of sparing them the hard life of working the fields and being accountable to his overseers who he paid for their ability to use violence to produce the extraordinary output that had made the Master so wealthy. It was also understood that having sex with the enslaved African women on the plantation was an unspoken perk of being an overseer. Again, this was one of the worst kept secrets of slavery, so if the Master knew that Sarah was in fact his daughter, he might’ve wanted to spare her from that, as well.

Sarah was described by the Adams as being a “model” slave. Before you consider that a compliment, please consider the situation. As I have discussed in previous posts, a slave is an identity. To be called a model slave is to say that Sarah met all of the expectations a master has towards a slave. Clearly, in order to do that, being a slave had to be something that you saw yourself as being through and through. And although I am sure he meant it as such, being a model slave is not a compliment.

When Sarah was 22 she had her first child, a daughter Louisa. Louisa is my third, great grandmother. The parentage of Louisa was never in doubt. She was the daughter of Joel R. Adams, the son of James Adams and Sylvia Goodwyn Adams. Louisa was much lighter than even Sarah the first of my relatives who could “pass” for white. After the passing of James Adams, my great grandmother Sarah was willed to his daughter Sarah Hopkins Adams while her mother Tenah and Big Frank were given to his son Joel R. Adams. Sarah Hopkins Adams died shortly after her father James, and Sarah willed Louisa to her biological father Joel R. Adams reuniting Sarah with her mother Tenah. Although Joel was a trained physician, he opted out of practicing medicine in favor of making a fortune running a plantation with slaves he had inherited from his family. It was here that Louisa had her daughter, Octavia, by a man named John Joseph Garrick. Octavia is my second, Great Grandmother (pictured).

Octavia was only 5 years old in 1865 when Union Troops arrived on the Adams Plantation and emancipated the Adam’s slaves from the only life they had known for the past 200 years. So although Octavia would’ve remembered being a slave, she would’ve remembered it through the eyes of a child. Understandably, very few former slaves readily admitted that they were ever slaves. Being a slave was not something that you would be proud of, even if it wasn’t by any fault of your own. Nevertheless, none of my family ever recall Octavia speaking about being born as someone’s property.

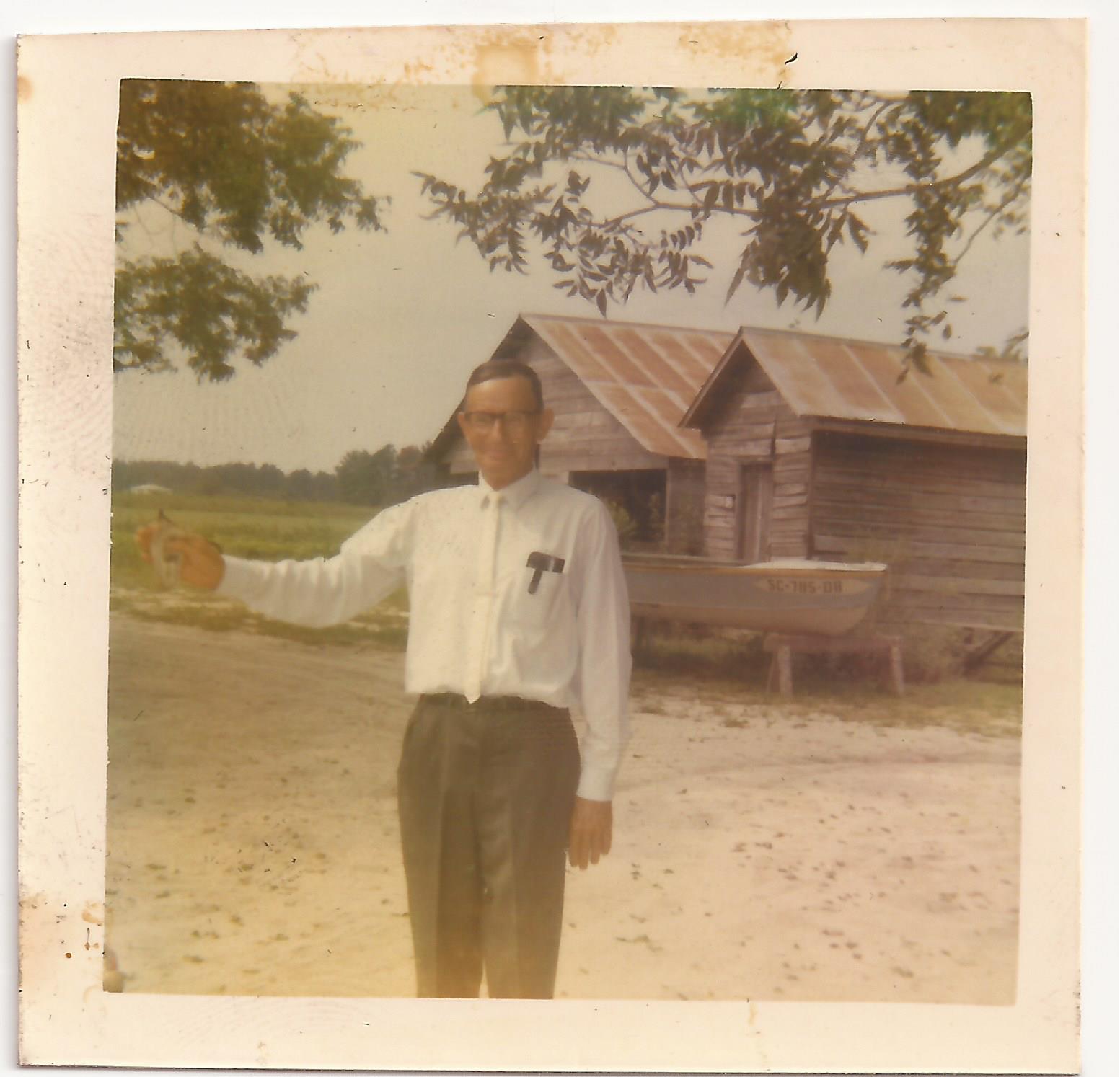

George W. Henry (pictured) was born on August 21, 1860 in Hopkins, South Carolina, three years before President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. His father, Samuel G. Henry was a white surveyor in the area. His mother was a mulatto named Mariah Lott, my third great grandmother. Mariah was NOT Samuel’s wife but most likely worked as a slave on his property. Mariah lived in a small house adjacent to where Samuel G. Henry raised his 8 children with his white wife Mary Ann. It was here that Mariah raised three boys, my second great grandfather George and his two brothers Lee and Steuben, probably all sons of Samuel G. Henry. I am unsure what kind of, if any, association George had with his White half-brother and sisters from his father and Mary Ann.

Remember, the typical Southern planter only owned four to six slaves. This was enough to make him several times wealthier than the typical southern non slave owner, but considerably less wealthy than those masters who owned 20 slaves. The Federal Government only allowed census takers to apply the title of “Planter” if the man owned a minimum of 20 slaves. That means that there were significantly more slave owners in the South than you would know by studying the census records scouring for the word Planter.

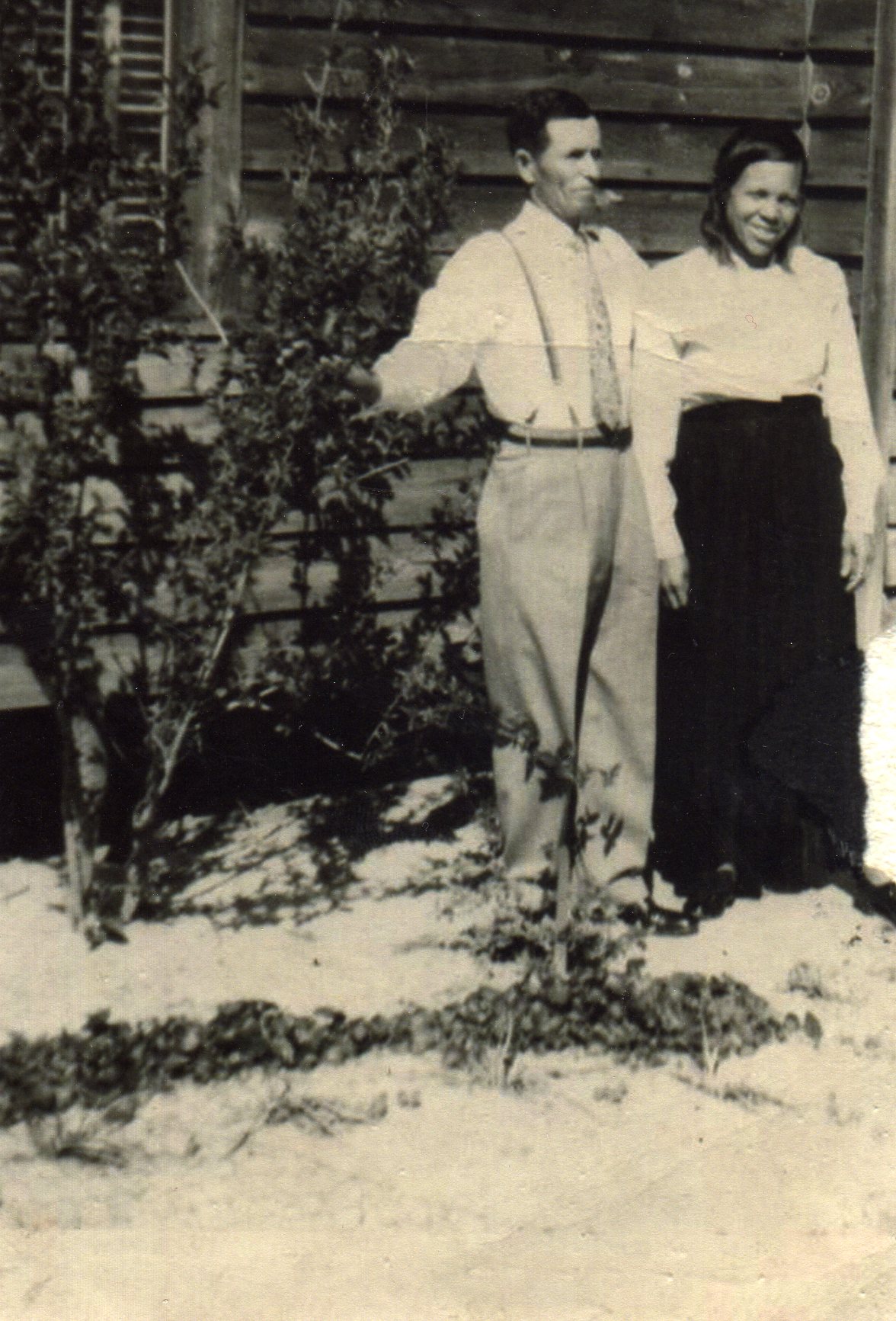

George W. Henry married Octavia Garrick (pictured) the granddaughter of Sarah, in 1886. The two of them had six children; five boys and a girl. Melvin (pictured), William (pictured), Heyward, Earl (pictured), James (pictured) and Hattie (pictured). James is my great grandfather. George and Octavia’s son Heyward has the unfortunate distinction of being the ONLY person from Hopkins, South Carolina to be killed in action during World War I. (His grave is pictured)

My great grandfather James was born in 1898. He married Josephine Taylor (pictured) in 1927. James, as you can see for yourself, could pass for white. He was also a college graduate and worked as a teacher for a while before devoting his life to building homes.

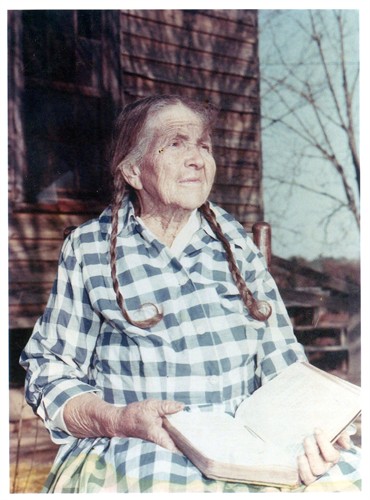

Josephine, his wife and my great grandmother, was half Congaree Indian. Unfortunately, Congaree Indians no longer exist. Josephine’s grandmother was Anna Ritter (pictured), a house servant for a German immigrant named Johan Huge Krause. Anna Ritter was my third great grandmother. Hugo and Anna had a daughter Lula Krause (pictured) who is my second great grandmother. Lula married Zachary Taylor, a black man, and together they had my great grandmother Josephine.

James and Josephine had 6 children, five that survived to adulthood. Heyward, James, Thomas, Lula & Marian. James (pictured) was my grandfather. We called him JD. JD came to Detroit to find work, following his Uncles William and Earl, where he met my grandmother Vivian Margaret (pictured), and they had three children, Linda, Darlene and Jimmy. Linda is my mother.

Source:

ALMOST FORGOTTEN: The Real America by Brenda Clarkson Turpeau